natural inks, pigments & environmental activism

about jules bishop

artist biography

Transforming landscapes into living inks and pigments, Jules Bishop works with natural materials at the intersection of art, science, and ecology. Her practice centres on the material behaviour of plant-based colour, producing drawings that continue to shift with light and time. These works emphasise the dynamics of organic pigments and the environmental conditions that shape them.

Liminality—particularly the transitions that mark seasonal change—forms a key framework for her research. She examines the moments when chlorophyll declines, colour values shift, and trees signal physiological change. Recently, her focus has expanded to acute forms of liminality generated by drought, heat stress, and environmental instability. Pigments produced under these conditions offer evidence of ecological pressure, raising questions about adaptation, resilience, and early indicators of environmental decline.

At the Broad Arboretum in Oxfordshire, Jules is mapping the chromatic behaviour of all 49 British native trees, documenting both their routine seasonal patterns and the disruptions caused by climate volatility. This longitudinal study informs works across drawing, print, sculpture, and video, each investigating how natural materials register environmental change and how colour can function as a diagnostic tool as well as an aesthetic one.

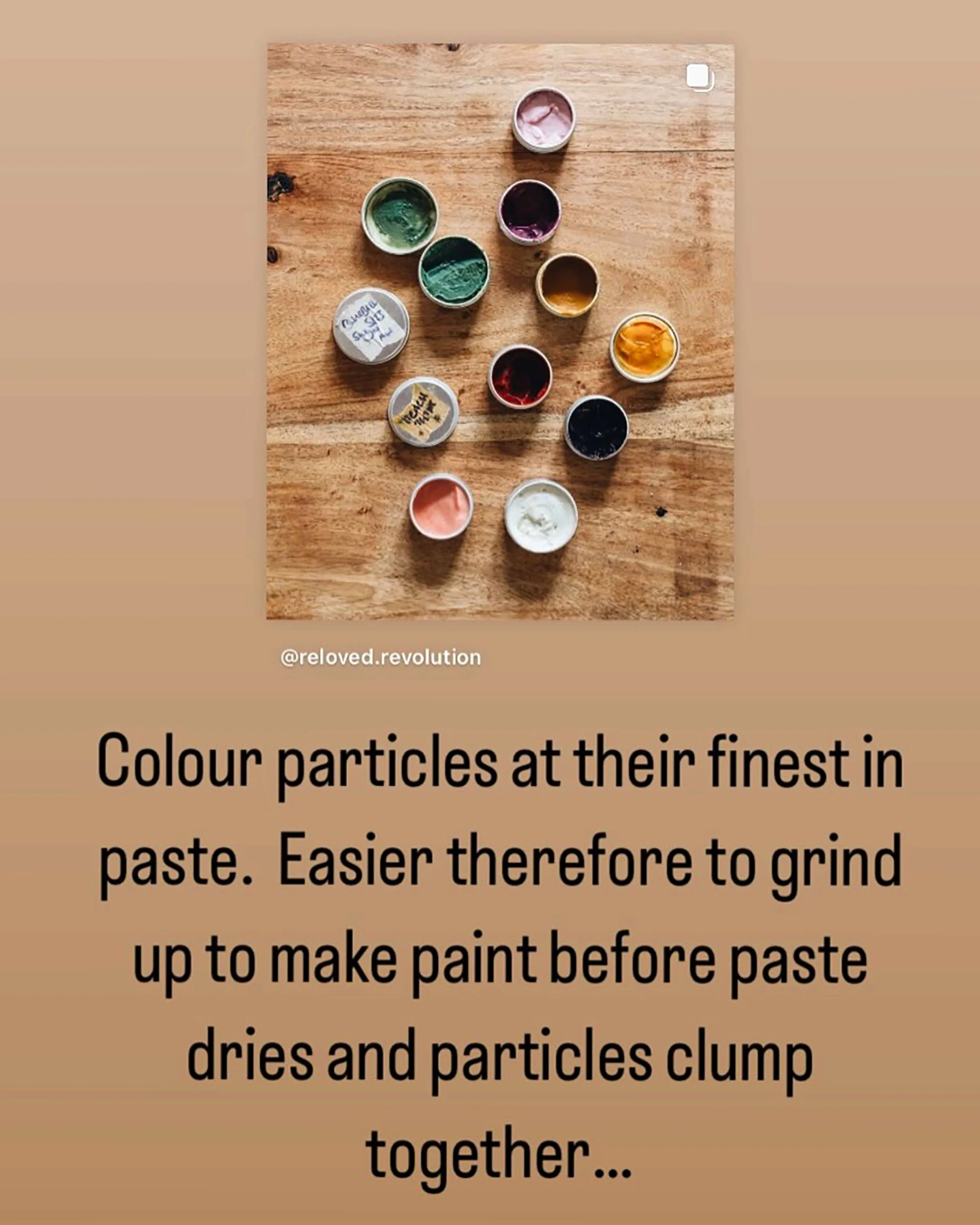

Jules has exhibited nationally, including selection for the Trinity Buoy Wharf Drawing Prize Exhibition 2021 (touring to Drawing Projects, Wiltshire, and The Cooper Gallery, Dundee). She has presented work at Oxford’s Natural History Museum, the University of Oxford Botanic Garden, and the Living Knowledge Conference 2022 in Groningen, Netherlands. She is a featured artist with Reloved Revolution in Oxford, where her ink-based works contribute to regenerative furniture design.

Actively involved in community arts and climate engagement, she is a founder member and current chair of Watlington artsHUB, art lead for the Watlington Climate Action Group, and a regular exhibitor in Oxfordshire Artweeks. She is also a member of the Plants & Colour Study Group (UK) and Pigments Revealed International (US), where she was invited speaker of the month in January 2024.

upcoming exhibition…

may 2026

Teaming up to form the WILD collective, artists Jules Bishop, Andrea Brewer, Mel Kelleher-Gannon, Maria Loring, Tom Robinson, Jo Smart, and Mick Venters are exhibiting together at the Watlington Methodist Chapel during Oxfordshire Artweeks 2026. Each artist engages with the natural world in their own unique way and will be transforming the Chapel into a wild haven of artworks.

The WILD collective encompasses a wide, eclectic range of media. These include drawings with local natural inks & pigments, stoneware ceramics, mixed-media artworks relating to the natural world, botanical prints on paper and clothing, specialised walking sticks, wildlife pencil drawings, and abstract wood carvings.

OPEN Saturday 2nd to Sunday 10th May, 11 am to 6 pm every day, 1 pm to 6 pm on Sundays